A maudlin celebration of the great dead of London’s Soho

“Nobody is healthy in London, nobody can be“, the hypochondriac Mr. Wodehouse says in Jane Austen’s Emma. Proverbially never healthy was Jeffrey Bernard whose weekly column in the Spectator was frequently substituted with the notice: Jeffrey Bernard is unwell. What began as a euphemism for the fact that Bernard was too drunk to write his column or even – which happened a few times – to resubmit an old column in the hope that it had been forgotten, in later years became a bitter truth. His “Low-Life” column which he had been writing since 1978 and which was generally held to be a suicide note in instalments, ended with Bernard’s death in 1997 after he had willingly stopped the dialysis necessary for his survival. That he had his own ideas about life, he had already made apparent earlier: Asked to write his autobiography he promptly put a small-ad in the New Statesman, enquiring whether anybody knew what his movements between 1960 and 1970 had been.

Born in 1929 and therefore three years Bernard’s senior was Sandy Fawkes, quite possibly the one of many ‘Ladies of Soho’ who could match the former’s alcoholic life-style. Like with many drinking buddies their friendship had its ups-and downs. The tragicomedy which takes place in the bars, pubs and clubs of bohemian Soho has something of what Walter Benjamin calls the eternal return – more recently known as Groundhog Day – and its protagonists are the regulars, the habitués who find themselves on more or less the same barstool every day. And as it should be in an alcoholic tragicomedy the boxing is without gloves and the fencing without masks. The much cited Anglo-Saxon reserve takes remarkably few glasses to disappear and the practice of good-natured (or not as the case may be) ribbing enters. Often the collision of differing characters is highly amusing, and the insults – richly peppered with ‘profanities’ – fly like tennis-balls. Sometimes the animosities, especially after the enjoyment of whisky which can make one a little maudlin are of a slightly more serious nature: the art of destroying an entire a life with a single, elegantly phrased, sentence requires just the right amount of Scotch. That then can seem a little tragic. The more so as the odour of failure and death is always slightly in the air. As Robert Louis Stevenson wrote: “Suicide took many, drink and the devil took care of the rest.” In Soho’s best known pub, the French House (the biography of which was written by Sandy Fawkes) the deaths and funeral arrangements of regulars are announced on a chalk-board. There were months when there seemed to be rather a lot.

The Scotch drinker Sandy Fawkes astonishingly enough hardly ever had a bone to pick with Jeffrey Bernard when she diurnally found herself on the stool next to him. Astonishingly as he had mentioned her often in his column and rarely in a flattering manner. In a TV-documentary from the nineties we see Bernard being asked by Norman, the landlord of the formers favourite pub The Coach and Horses whether anything out of the ordinary happened the previous night. “Nothing“ answers Bernard, “Sandy Fawkes was pissed”. Groundhog Day. Yet the two had even worked together in the sixties. Fawkes had done some research for Frank Normans unjustly forgotten book Soho Night and Day for which Bernard provided the photographs.

It was in Soho – still the corner of London where people look first for pleasure and then for oblivion – that Bernard and Fawkes spent most of their lives. The square mile enclosed by Charing Cross Road, Shaftesbury Avenue, Regent and Oxford Street with its plethora of cafés, restaurants and drinking establishments has been a place of refuge for eccentrics and outsiders from all corners of the earth since Charles II. released the Soho Fields for development in 1675. In the second half of the 20th century Soho attracted not only gangsters and prostitutes but also a motley crew of painters, writers and hedonists. They gathered in pubs like the York Minster, the Coach & Horses or clubs like the Caves de France and the Colony Room. Few of them managed to combine excessive drinking and concentrated work like the painters Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud.

Bacon and Freud were regulars of the Colony Room, the legendary afternoon drinking club which had been founded in 1947 by the Birmingham Jewess Muriel Belcher. On the opening day of her club Muriel made the acquaintance of the young Francis Bacon and promptly employed him as a ‘hostess’: For the princely sum of 10 pounds a week plus free alcohol consumption, Bacon brought rich drinkers to the Colony. Bacon and Muriel became close friends an later on she also posed for him sometimes. As there was a curfew on public alcohol consumption between three and seven in the afternoon until 1988, a drinking club was of the essence to those who did not want their drinking-and working hours to be reglemented by her Majesty. Hence the olden Soho days could be quite long. The Afternoon Men (and women) invoked by the writer Anthony Powell had often drunk deep from the blue of noon by the time the pubs opened again at 19.00. At this hour Bacon usually disappeared into the night in order to paint through it in his South Kensington Studio.

For others the draw the fleshpots of Soho exercised on them was more or less the only purpose in life and proved fatal in the end. Bernard could easily have said with the Chinese sage Li Po: “ Thirty years I hid my fame in taverns.” Indeed he was granted late fame: In 1989 the play of his life named after his eponymous column Jeffrey Bernard is unwell by Keith Waterhouse was premiered. The lead was taken by Peter O’Toole.

Despite an inauspicious start Sandy Fawkes life was equally not without its exciting and even glorious moments. Just a few weeks old she was found by the Grand Union Canal where she had been abandoned by her mother. Various foster parents followed, some abused her. Despite all of this she grew up to be an intelligent and artistically gifted teenager and secured a place at Camberwell School of Art for herself. Her teacher there was John Minton, an inspiring painter who was in the habit of packing his students in a bus and taking them to Soho. It was here – in the French House (the York Minster back then) that Sandy took her first alcoholic drink a Gin with orange cordial: “Maybe I should have renounced alcohol that very day”, she was later to say, “ but I would have missed out on many pleasurable days and friendships. Disasters too.”

Also through John Minton, a Jazz-fan she met Wally Fawkes, a clarinettist and cartoonist in the late 1940s. They married in 1949. They had four children, one boy and three girls, one of which tragically died in infancy. They divorced in the early 1960s whereupon Sandy took up drawing again. She did fashion drawings for Vanity Fair and others and having established herself in the press changed to writing in the 70s. Amongst many assignments, she reported from the Yom-Kippur war for the Daily Express of which she was very proud. This was followed by a less salubrious episode. After a failed trial with the National Enquirer, she met a handsome young man in a bar in Florida. They started a relationship and she accompanied him for a week ‘on the road’ in the general direction of Florida. A few days after they separated he was arrested. It turned out Sandy had been sleeping with the serial-killer Paul Knowles who had committed two murders on the day the two met alone. Why he had chosen to spare her, Sandy never knew.

On her return to England she was ready to take up permanent residence on the barstools of Soho – doubtlessly also somewhat shell-shocked by her narrow escape. A life full of ‘fun’ and long lasting kinships of one’s own choosing which all too often also mirrored the hierarchies of ‘real life’: Until today the regulars in the French House are sat to the right of the bar, a position that can only be achieved through decades of hard drinking. Sandy had earned respect: When Sandy took up position in late morning, the employees of the French House brought her the morning papers and the medication she needed. She still wrote a few factual books, one about her week with Knowles, but mainly her life took place on the stage of two Soho pubs and a few drinking clubs. Her wardrobe was equally stuck in the seventies which doesn’t mean she was without elegance. Quite the opposite: Her fingernails between which sat the eternal Gitane, were always polished spotlessly and her infamous fur-hat which she wore throughout most of the year has adorned the bar of the French House since her death in 2005.

Now that the magic of Soho is being eroded street by narrow street through corporatism one recalls the words the writer Colin Macinnnes used to describe its draw with poignant nostalgia: “… a senseless fascination with forbidden fruit, the intoxication of an invented romantic Baudelairean evil”. Phantasy indeed plays a large part in the relationship the English have with alcohol. More than the drinking itself the Englishman/woman loves talking about it afterwards. How much was drunk, how thoroughly one disgraced oneself, how profoundly the hangover is (Kingsley Amis distinguished between the physical and the metaphysical hangover). The delicious feeling of doing something forbidden is enhanced by closing time – drinking against the clock before being caught out. On the whole one stays in the pub until it closes. The Frenchman might savour a glass of wine for hours, the Englishman drinks to get drunk.

Due to the use of hyperbole in the description of alcoholic excesses, it is hardly surprising that the French generally think of the English as drunkards. Already Barbey d’Aurevilly mistakenly describes his protagonist as a drunkard in his metaphysical biography Du dandyisme et du Georges Brummell and thereby confounds two English traditions: Hard drinking and dandyism. But there are indeed some parallels: Like the dandy, the drinker seeks to realise himself beyond the profane world of toil. The desperate search for meaning leads the dandy towards reductionism: “Presses de trouver le lieu et la formule” – the correct suit, the perfect bon mot. Jeffrey Bernard once formulated the height of his worldly ambition: “A pinstripe suit, a girl on my arm and enough money in my pocket to spend the day in the Coach and Horses.” The Coach is now under new management and the Colony Room died a decade ago along with its last proprietor. “Beautiful as the tremor of the hands in alcoholism” writes Lautréamont and a life-style choice of more or less enjoyable alcoholism will survive in London even though the old guard has long finished its last drink.

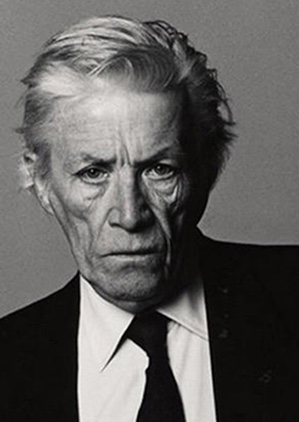

Featured Image: Jeffrey Bernard (Via)